Author

Ignore the evidence at your peril.

It might seem an obvious thing for a lawyer to say but the judgment of the Court of Appeal in the Lidl -v- Tesco Clubcard logo case is a classic example of lawyers’ unwillingness to accept real world evidence from “average consumers” could be determinative of the issues.

Lord Justice Arnold said in his conclusion “At first sight, the judge’s finding that a substantial number of consumers would be misled by the Clubcard Price Signs into thinking that Tesco’s Clubcard Prices were the same as or lower than Lidl’s prices for equivalent goods is a somewhat surprising one. As Tesco emphasise, the Clubcard Price Signs make no reference either to Lidl or to pricematching, they are a part of promotion concerning Tesco’s own prices for Clubcard holders and they are quite different to the contemporaneous Aldi Price Match signs.”

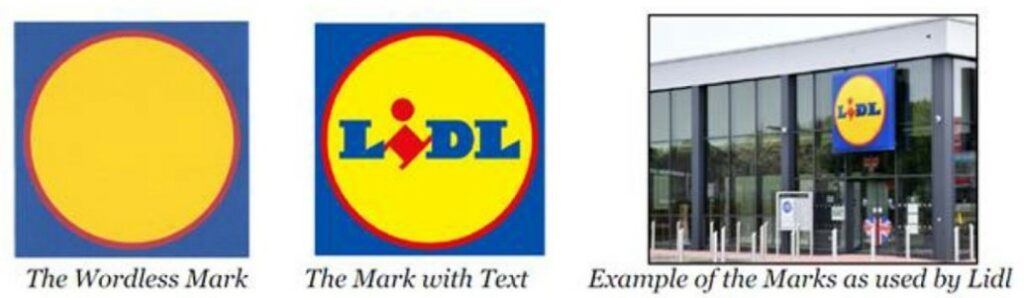

The problem is that lawyers looking at cases such as these see the images side by side like this:

The lawyers see the obvious differences (including in this case the competing trade mark “Lidl”) and cannot see any other point of view.

The problem with this approach is that the lawyers have forgotten that the correct test is one of “imperfect recollection” which recognises that the average consumer rarely sees the two competing marks side by side.

Moreover, in this case there was a body of evidence which consisted of spontaneous reactions from consumers who mentioned Lidl when presented with the Clubcard Price logo on its own. These consumers mentioned things like ‘Tesco price matches against Lidl’ and ‘price match Lidl on most things’ which showed that consumers not only established a link between Lidl and Tesco but moreover believed that the Clubcard Price Logo incorporated one of Lidl’s central advertising messages; namely, that Lidl offered cheap prices which Tesco price matched.

Arnold LJ carefully reviewed the findings of the first instance judge, Mrs Justice Smith, noting which were under appeal and which were accepted by Tesco. He noted how carefully she had balanced all the evidence and, save for one small immaterial element, stated she had not placed too much emphasis on any part of the evidence in reaching her findings. He concluded “The judge was not only entitled to place some weight on each of those strands [of evidence], but also to regard each of the three strands as reinforcing the other two. …The judge took into account, as Tesco urged to her to do, the general problem of misattribution in the industry and Tesco’s evidence that they intended to convey a clear message about Clubcard Prices, and she was entitled to conclude that neither point was a complete answer to Lidl’s case.”

The really important learning for anyone with an interest in brands and trade marks is to note Arnold LJ’s conclusion that “it is not unknown for judges hearing passing off cases to make findings of deception that seem surprising to lawyers and judges who, unlike ordinary consumers, are aware of the issue and who have not heard the evidence.“. Further, the Court of Appeal found the first instance judge had made rationally supportable findings based on the evidence in respect of the trade mark infringement allegation and therefore dismissed both of Tesco’s appeals.

Lewison LJ, one of the other Court of Appeal judges admitted to finding the case “difficult”. He referred to three cases in which the author of this piece was personally involved: Interflora v Marks & Spencer; L’Oréal v Bellure; and Specsavers v Asda relating to the infringement of trade marks by taking unfair advantage of the reputation of the mark. In agreeing with Arnold LJ, Lewison made his own surprise even clearer saying that he doubted he would have come to the same conclusion as Mrs Justice Smith. Then quoting the Jif Lemon case, he concluded “If I could find a way of avoiding this result, I would. But the difficulty is that the trial judge’s findings of fact, however surprising they may seem, are not open to challenge. Given those findings, I am constrained … to accept that the judge’s conclusion cannot be faulted in law.”

Therefore, Tesco’s passing off and trade mark appeal failed and so Tesco will now face the prospect of removing all the Clubcard Price logos from their stores nationwide.

What do we learn?

While trade mark judges are more than willing to stand in the shoes of an average consumer and decide trade mark infringement matters and passing off cases from their own experience, such judges will equally accept evidence from real consumers.

In the past, cases such as these have been dogged by attempts to “find” evidence through surveys and witness collection exercises leading some practitioners to conclude that the “average consumer” cannot be found in the real world; after all it is “average consumer” test is a legal construct of a mythical person who is “reasonably well informed and reasonably observant“.

However, careful practitioners who piece together multiple strands of spontaneous reactions from members of the public (members of the public who are then traced and brought to court) can establish the genuine impact of branding on consumers. Such spontaneous evidence from members of the public is not statistically significant. It is not even quantitatively the “tip of the iceberg”. BUT what it is, is real-life, qualitatively evidence of how a consumer, unsullied by years of legal training, sees the world.

Mrs Justice Smith was entitled to place reliance on all this evidence as a whole and conclude that it pointed in only one direction – each piece reinforcing the other but no piece being determinative of the issues – to find that Tesco infringed Lidl’s trade mark and was liable for passing off.