Authors

The Intellectual Property and Enterprise Court (IPEC) waved goodbye to dry January this year with its judgment which undoubtedly will have come as a blow to Aldi; the IPEC held that Aldi’s Infusionist gin liqueur amounted to an infringement of protected designs of M&S’s light up gin liqueur range.

This IPEC decision is a rare win in the world of look-a-like products. All supermarkets love a look‑a‑like from Asda’s puffin bars[1] to Aldi’s Miracle Oil, usually brand owners end up on the wrong side of a decision when trying to enforce their rights. However, this case shows that there is a line not to be crossed when seeking inspiration from products on the market. The case is a reminder of the importance of doing your due diligence, and helpfully notes what should be considered for the test for infringement of a registered design.

Background

Many readers will be familiar with M&S’s gin liqueurs which have frequented its stores annually in recent years, particularly in the run up to Christmas. Since M&S’s gin liqueur range first launched, various designs have been unveiled, including the use of LED lights in the base of the bottles to illuminate gold flakes contained within the product itself. The designs of these bottles are protected by registered designs since April 2021 (the RDs), which confers a 25-year monopoly right in the design.

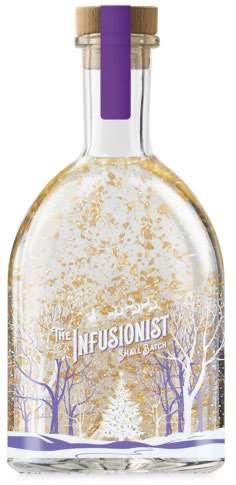

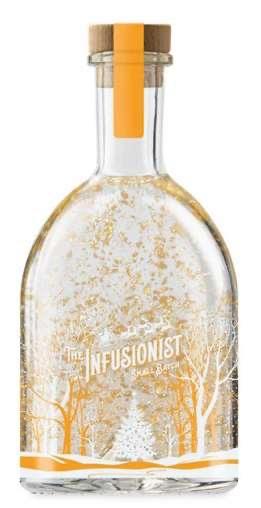

In November 2021, Aldi began to sell the following gin liqueurs also containing gold flakes as part of its ‘Illusionist’ range:

The Dispute

In short, M&S brought proceedings against Aldi for infringement of the RDs:

Under the Registered Designs Act, the registration of a design gives the registered proprietor the “exclusive right to use the design and any design which does not produce on the informed user a different overall impression“. Consequently, a design will infringe a registration if it does not produce on the informed user a different overall impression to that produced by the design as registered.

The scope of protection for the registered design depends on the image filed with the registration and what it shows. Get this part wrong and your rights will be seriously compromised as the makers of the Trunki suitcases found to their cost despite blatant copying. Usually, a photograph of the product (rather than a line drawing for example) will diminish room for error in interpreting the design features. However, in order to ensure as wide a scope of protection as possible, rightsholders often file line drawings with fewer specific features as well. As noted above, in this case a key element of the product was the use of LED lights. Each of the RDs note in their description that the product is a “Light Up Gin Bottle”, although both parties, and indeed the judge, HHJ Hacon, considered that the description was irrelevant to the interpretation of the designs.

Aldi relied on the following differences:

- The winter scene of the RDs is in white only and features a stag and a doe. On the Aldi bottles the scene is in white and a colour with trees only.

- The Aldi bottle has the “Infusionist” branding. Conversely, the RDs have none.

- The foregoing two features of the Aldi bottle give it a front. There is no front to the RDs in suit.

- The Aldi winter scene is ‘brighter’ and ‘busier’ than that on the RDs in suit.

- The Aldi stoppers have a watch strap label with the Aldi logo on the top, the RDs in suit do not.

- The Aldi stoppers are darker in shade than those of the RDs in suit.

Interestingly though, no counterclaim for a declaration of invalidity of any of the RDs was pleaded in this case, despite frequently being the ‘go to’ approach for defendants in design infringement proceedings. Presumably, Aldi had tried to find evidence that the M&S designs were not new when registered but had not been able to produce any previous designs on which the M&S RDs were based.

The Decision

Both parties adopted a four-stage approach in comparing the designs for the court’s consideration. As in previous case law, the court:

- Decided the sector to which the products in which the designs are intended to be incorporated or to which they are intended to be applied belong e.g. liquid products sold in decorated bottles, products which may contain gold flakes;

- Identified the informed user and having done so decide (a) the degree of the informed user’s awareness of the prior art and (b) the level of attention paid by the informed user in the comparison, direct if possible, of the designs;

- Decided the designer’s degree of freedom in developing his design;

- Assessed the outcome of the comparison between the RDs and the contested design, taking into account (a) the sector in question, (b) the designer’s degree of freedom, and (c) the overall impressions produced by the designs on the informed user, who will have in mind any earlier design which has been made available to the public.

Similarities noted between the two parties’ products included the shape of the bottles and stoppers, the ‘snow effect’ produced by the use of the LED lights, and the ‘wintery scene’ applied to the bottles.

As a result, the Judge concluded that Aldi’s bottles did not produce a different overall impression, and that the differences noted above which Aldi relied on were ‘of relatively minor detail’, whereas the similarities between M&S’s registrations and Aldi’s Infusionist products were more ‘striking’. Consequently, it was held that Aldi had infringed M&S’s RDs and their exclusive right to use the design and any design which does not produce on the informed user a different overall impression.

Observations

As a discount supermarket, Aldi has arguably been at the epicentre of legal disputes regarding copycat products for years now. Most recently, the #FreeCuthbert dispute between also M&S and Aldi (articles here and here) which highlighted the growing importance of a well‑considered PR strategy alongside a sound legal strategy. Whilst this case has not enjoyed the same social media coverage as the #FreeCuthbert campaign, it does act as a timely reminder to rights owners of the importance of a proper IP strategy with regard to all types of IP protection. Commercially, having a design registration is likely to be the most powerful tool to stop look‑a‑like products and may also help to build a reputation and goodwill for a product, which coupled with a registered trade mark, puts rights owners in the strongest position.

While this decision will be welcomed reassurance for designers who use registered designs to protect their products, you only need to walk down any supermarket aisle to realise this case will not stop Aldi and its compatriots from producing look‑a‑like products.

*Images obtained from IPEC judgment.

[1] United Biscuits (UK) Ltd v Asda Stores Ltd [1997] RPC 513