Background

Multinational Enterprises (MNE’s) are enterprises (or corporations) that produce goods or deliver services in multiple countries. To do this, the MNE commonly has a group company structure with a parent company in the ‘home’ country of the MNE and subsidiary companies abroad.

Claimants may wish to bring an action against a parent company of an MNE in respect of a wrong committed by a subsidiary company in the ‘home’ country of the MNE for reasons including that: the home country may be perceived to be a preferential forum due to the procedural rules of that forum; the perceived expertise of legal professionals providing services in that jurisdiction; and to inflict greater reputational damage on the MNE due to the fact the parent company may be more high profile than the subsidiary.

One of the problems with a claimant attempting to sue a parent company for a wrong committed by a subsidiary company in a different country is posed by the doctrine of limited liability for shareholders. Limited liability is a consequence of a corporation’s separate or independent legal personality. The doctrine of limited liability applies in most common law and civil law countries in the world and was affirmed to apply in international cases by the International Court of Justice in Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited [1970]. The doctrine of limited liability, as traditionally understood, would mean that a claimant would find it difficult to sue a parent company for the actions or wrongs committed by its subsidiary, as it would logically follow that the subsidiary was a separate legal entity to the parent and the parent company (being a shareholder in the subsidiary) would be protected by the doctrine.

The doctrine of limited liability does however have exceptions where a shareholder can be made liable. One of these potential exceptions is the issue of ‘non-adjusting’ or ‘involuntary’ creditors i.e. victims who suffer damage as a result of a wrong caused by a company which the victim did not volunteer to deal with. The area of environmental law and its associated claims in tort (such as negligence and/ or nuisance) may give rise to involuntary creditors who suffer loss and which may give rise to circumstances in which a shareholder parent company can be held liable.

This article considers the implications for MNE’s and whether parent companies can be held liable in respect of actions which more obviously appear to have been taken by subsidiary companies in tort by reference to the Okpabi judgment.

Okpabi v Shell [2021]

The case concerns two sets of proceedings, brought by or on behalf of residents of Bille and Ogale in Rivers State, Nigeria.

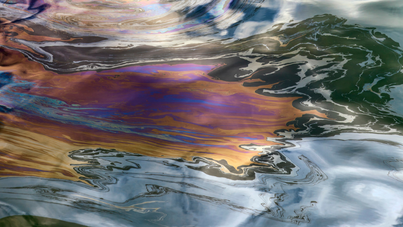

The claimants’ case is that oil spills have occurred from oil pipelines operated negligently by the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC). SPDC is a Nigerian registered company and a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell (RDS), a UK domiciled company and the parent company of the ‘Shell’ group of companies.

The claimants issued proceedings in the English courts against both SPDC and RDS relating to the actions of SPDC. The claimants however allege that RDS (as the parent company) is liable for the actions of its subsidiary SPDC.

At an early stage, the defendants challenged the jurisdiction of the English court. The key issue to be determined was whether the claimants’ claims against RDS raised ‘a real issue to be tried’ meaning whether the claims against RDS had a real prospect of success.

The first instance court and the majority of the Court of Appeal held that the claimants had no arguable case that RDS owed them a duty of care to protect them (or compensate them) for damage caused by SPDC, RDS’ subsidiary.

On appeal, the Supreme Court allowed the claimants’ appeal and found that the claimants’ claims against RDS did raise a ‘real issue to be tried’ and had sufficient prospects of success to continue. Notably, in coming to its findings, the Supreme Court endorsed the dissenting judgment of Lord Sales in the Court of Appeal noting that: ‘It is of significance that the Shell group is organised along business and functional lines rather than simply according to corporate status. This vertical structure involves significant delegation’. The Supreme Court found that the RDS governance framework demonstrates that the RDS CEO and other members of senior management has ‘a wide range of responsibilities, including for the safe condition and environmental responsible operation of Shell’s facilities and assets’. These quoted excerpts provide an insight into the Supreme Court’s reasoning as to how the claimants’ claims could not be dismissed at an early stage on the basis of the claims against RDS having no real prospects of success. In essence, the Supreme Court are entertaining the possibility that the claimants’ claims against RDS may have merit on the basis of the degree of influence RDS exerts over SPDC’s operations, despite SPDC being a separate legal entity with the consequence of limited liability for its shareholder RDS.

Conclusion

It should be noted that the Supreme Court decision merely relates to the arguability of the claimants’ claims. The Supreme Court were willing to find that, prima facie, on the claimants’ pleaded case, the claimants’ claims against RDS have sufficient merit to proceed without being subject to early disposal. The Supreme Court made a point of not conducting a detailed examination of the evidence in the case, this being one of the errors of the approach adopted by the Court of Appeal in conducting a ‘mini-trial’. This decision therefore demonstrates that it is arguable that victims of a wrong can include a parent company to an action brought against the subsidiary (whom more obviously is the entity associated with committing the wrong). The decision is no guarantee that the claims against RDS will be successful which will be dependent on a full trial. The development of the Okpabi matter (which is ongoing) will be of interest to MNE’s as well as victims of environmental wrongs caused by MNE’s.