Authors

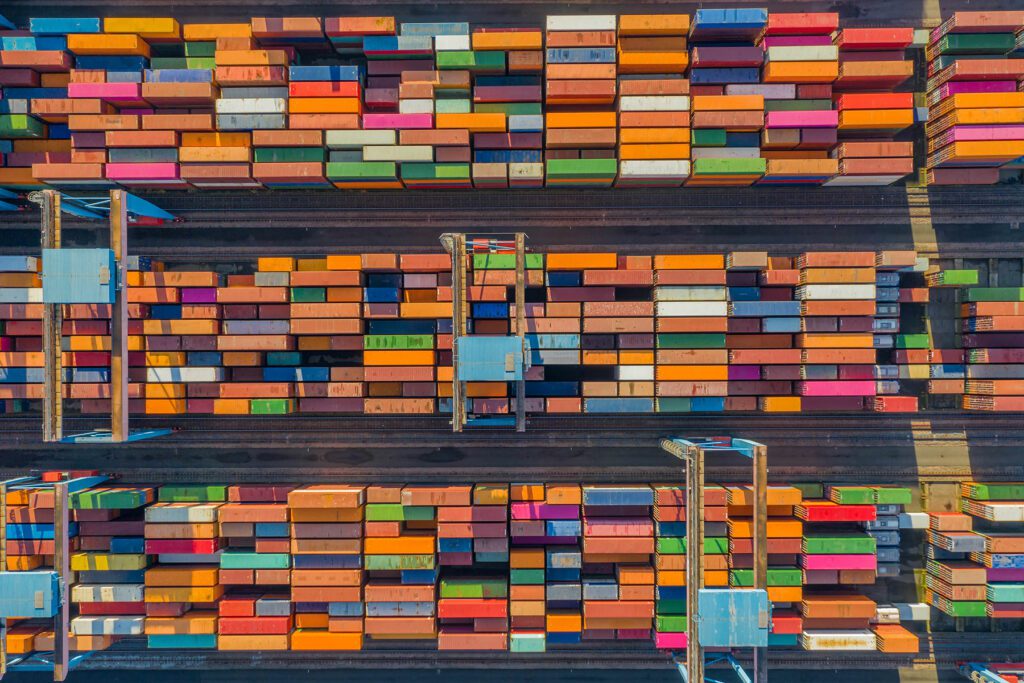

Increased costs and economic uncertainty caused by the Trump administration’s tariff regime increase the probability that suppliers and buyers alike may seek to wriggle out of existing contracts as increased costs reduce the commerciality of what might have once been a good deal. It is anticipated that this will result in more contractual disputes.

The tariffs will inevitably have a detrimental impact on international supply arrangements as well as contracts between companies in the same jurisdiction (1) that are reliant on components from the USA or (2) where the end market for their product is in the USA.

Suppliers and buyers alike may seek to rely on force majeure clauses contained within their contracts.

What is force majeure?

“Force majeure” clauses are specific, defined clauses which serve to excuse parties from performance of contractual obligations where that performance is significantly impacted or made impossible by events outside of their control, such as a pandemic or an earthquake.

The parties to the contract can negotiate what constitutes a force majeure event. As recent events have shown, it is essential for parties negotiating tariff-sensitive commercial agreements to factor tariffs into force majeure clauses.

Typically, a force majeure clause in a supply of goods agreement would set out clear events that can frustrate performance of the contract, which might include “governmental action” that renders the contract impossible to perform. The wording for such a clause may be something along the following lines:

“Any law or action by a government or public authority, such as the imposition of a quota, prohibition or restrictions on export or import”

This article will look at the extent to which tariffs might be covered in force majeure clauses, and the options that might be available to parties.

Potential frustration: making parallels with Brexit

A comparable situation with widespread international and commercial ramifications was Brexit. Between 23 June 2016 (the date of the Brexit referendum) and 31 December 2020 (when the UK left the EU) there was uncertainty around tariffs and numerous cross-border pre-existing commercial contracts stood to be affected.

The Court’s position at the time was clarified in a dispute relating to the 25-year lease for the European Medicines Agency (EMA) premises in Canary Wharf. The EMA’s lease began in 2011, contained no break clauses and the property had been fitted out ahead of the 2016 vote. The Court was clear that (1) economic uncertainty and increased expenses following an event such as Brexit did not render the contract impossible to perform and (2) a force majeure clause must be very carefully drafted if frustration due to a specific event is to be asserted (in this example to cover the possibility of Brexit and future economic burdens of contractual performance). The Court will also consider the common purpose underlying the contract.

An alternative route to argue might be commercial impracticability, which carries the slightly lesser burden of performance having been rendered infeasible and not reasonably achievable, as opposed to impossible or radically different. While beyond the scope of this article, it’s an avenue worth considering.

Working with existing force majeure clauses

Contractual performance may be excused if tariffs are included in the force majeure clause. The Court will expect a force majeure clause to expressly identify the type of event in question before it will consider a contract’s performance to have been frustrated because of the occurrence of that event. Even where the event is expressly identified in the clause, it is a significant risk to unilaterally claim that the contract is frustrated if the contract could still technically be performed and the event has simply altered the benefit of the contract or made it harder to perform.

For example, in the case of the outbreak of war (even when ‘war’ is included as a force majeure event in an agreement) it has been said that it is not the formal declaration of war itself but certain acts of war which might prevent performance of a contract.

The Courts took a similar approach in COVID-19 to leases as in the Brexit Canary Wharf case – in one instance, it was not accepted that three aircraft leases had been frustrated by the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, on the basis that the leases had been drafted such that the obligation to pay rent was “absolute and unconditional irrespective of any contingency whatsoever“. Likewise, in a business interruption insurance case, the Courts took the view that a rent cesser clause did not operate absent physical damage to the premises.

While the clause may not need to specifically use the term “tariff”, a court would likely rely on a variety of factors to ascertain the parties’ intentions including:

- Judicial decisions considering similar language;

- The parties’ usual practices and prior dealings; and/or

- Language used in the contract.

There may also be other angles that parties can explore:

- Changes in law – such clauses are often (but not exclusively) found in construction or supply contracts pertaining to construction projects and these could be triggered by increased tariffs.

- Changes in circumstance – such a clause might allow for outright termination if the effects are serious enough. As a first port of call parties could rely on changes in circumstance to renegotiate terms of contracts to compensate for the increased costs caused by tariffs.

- Ex-party applications – if the actions of third parties following tariff increases impede performance, mechanisms such as preliminary injunctions to require a third party to perform their obligations pending resolution via litigation can be sought.

Futureproofing

The likelihood of force majeure clauses providing relief in tariff-related circumstances can be improved at the drafting stage, for example by:

- Creating a precedent clause that specifically defines the imposition of new and increased tariffs as a force majeure event;

- Lowering the contractual threshold for relief;

- Setting out whether the clause should operate to benefit both the supplier and the buyer, or just one of the two;

- Including effective dispute resolution clauses that encourage initial dialogue and/or swift resolution over escalation; and

- Considering the inter-action of a force majeure clause with coverage under a business interruption insurance policy (which could span pandemics, cyber threat or tariffs amongst other external factors causing market volatility).

If you find yourself in a situation where a business you are contracted with is trying to allege force majeure, or if you are seeking to assert it, please contact Nick Roberts or Sophie Uyttenhove.